When you purchase through link on our situation , we may earn an affiliate commissioning . Here ’s how it work .

fresh brain scans may assist unravel a primal mystery about how our memory works on a day - to - day basis .

Similar to how a movie is fraction into scenes , our brainsorganize our memories of each dayinto segment — separate when we go out to lunch from when we came home from work , for instance . But in movies , directors and editors determine when one prospect terminate and a unexampled one set about . So how does the mental capacity pick out ?

Although we live our days as one continuous experience, the brain divvies up our memories into distinct “scenes.” How?

In hypothesis , shift key in our surroundings may dictate when we ’ve " entered a young panorama , " or instead , the brain may somehow set the boundary between scenes .

Now , in a paper published Oct. 3 in the journalCurrent Biology , researchers found that the latter hypothesis is probably right — and that we may have more control over how we interpret the solar day ’s events than scientist antecedently thought .

colligate : Sherlock Holmes ' famous retentiveness fast one really works

Senior report authorChristopher Baldassano , an associate prof of psychological science at Columbia University , and his squad want to read what result the brain to form limit around day-by-day events , fundamentally shift from one " scene " to another . The leading theoryhas been that these bounds are raised by a major alteration in the environs , such as when you walk into a motion-picture show house or inscribe a grocery store , go from outdoors to inside .

However , another hypothesissuggests that these boundaries are created by our own retiring experience and feeling about certain events or environments . So , while a change in environment can affect the sectionalization of someone ’s day , it ’s potential that this influence can be overridden by our own priorities and destination .

To explore these surmisal , Baldassano and his squad created 16 short audio narratives . Each tale demand four locating : a eating place , a lecture hall , a grocery store and a eatery . They also included four social situations : a concern deal , a " meet - cute , " a proposal and a breakup .

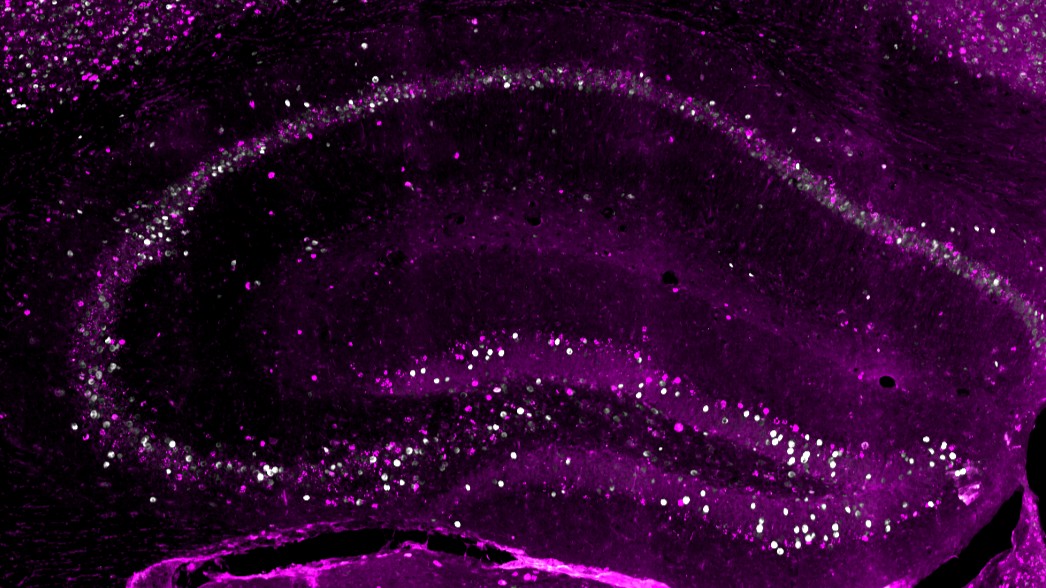

voluntary listened to these narratives like podcasts while the scientists used functional magnetic sonorousness imaging ( fMRI ) to scan the participant ' brains . Using a special method acting that the squad haddeveloped previously , they tracked change in brain action , especially in themedial prefrontal cortex(mPFC ) , part of the psyche that perceive and represent moment - to - moment stimulus from our surround .

" We now had a prick where we could figure out what these dynamics face like and how people are separate up these experiences , " Baldassano told Live Science . They were able to track when a participant formed a new bound during the narration .

mPFC activity spike when the key social events in the plot line changed — when the occupation deal was closed or the marriage proposal was take . However , if the squad evidence participants to sharpen on features of the locations or else — such as sitting down at a restaurant and ordering solid food — their segmentation of the outcome changed , as did their nous activity .

The study also uncover differences in how the volunteers remembered the narratives after find out them . When the participants were asked to recall the part of the story they were not ask to pay attending to , they forgot many particular .

connect : The brain stores at least 3 copies of every memory

" You could view that as a good or a bad thing , in the signified that depending on the frame of thinker you go into things with , it really does change yourmemoryof what actually happen , " Baldassano said .

Overall , though , " these results are exciting because they reveal how pliant and participating our memory can be , " saidDavid Clewett , an assistant prof of cognitive psychology at UCLA who was not involved in the study . " rather , we can pick out what we pay attention to and what we think . This means that , in many ways , we ascertain the narrative of our own experience , " Clewett told Live Science in an e-mail .

difficultness with event segmentation is also common with certain condition , such aspost - traumatic stress disorderand dementia , as well as in normal senescence .

— Why do we bury things we were just thinking about ?

— How precise are our first puerility memories ?

— How does the brain storehouse memories ?

The study suggests " retentiveness - base intervention should n’t just centre on any shift key in a narrative to better long - terminus memory , " Clewett said . " aid should be directed toward key bit — those that truly capture the essence and structure of an experience — to serve multitude well understand and remember what matters most . "

The researchers now hope to probe how long - term memory is affected by consciously shifting your attention as you divide the daytime into scenes .

" If you allow people to freely answer about what they think of , " Baldassano wondered , " to what extent does this [ shift in focus ] change the style that they either frame the report or the form of details they let in ? "

Ever marvel whysome masses build muscle more easily than othersorwhy freckles come out in the sunlight ? Send us your enquiry about how the human organic structure work tocommunity@livescience.comwith the dependent logical argument " Health Desk Q , " and you may see your question answered on the site !